by STEFAN VOICU.

On the 1st of February around 150.000 people took the streets of Bucharest and another 150.000 the streets of other Romanian cities. Some say it was the biggest mass mobilization since the one in 1989 which led to the overthrow of Nicolae Ceaușescu’s regime. The reason behind these manifestations was the decree issued by the newly appointed government on the night of 29th of January regarding changes in the criminal code. This moment was the great rupture of an event unfolding from mid-January when the law changing project and an associated pardoning project gained media attention and protests were organized against them. Two weeks before the issuing of the decree 40.000 protesters rallied on the streets of Bucharest, and a week later the number rose to 90.000. Even during the night the government issued the decree 15.000 occupied Victoria Square, where the Government Palace is located. On the 2nd and 3rd of February people continued protesting in growing numbers, reaching on 5th 250.000 only in Bucharest and 600.000 in the entire country.

Most protesters are resentful of the decree and the pardoning project because the pardoning would lead to the release of some politicians convicted in the past years by the National Anti-corruption Agency (DNA – Direcția Națională Anticorupție) and the changes to the criminal law could decriminalize official misconduct acts whose financial damage is valued at less than approximately 45.000 euros. More than that, the decree could favor the leader of the Social Democrats Party (PSD – Partidul Social Democrat), Liviu Dragnea, who was convicted for vote rigging and who could not become prime minister because of this reason, although the party he’s leading won the parliamentary elections of December 2016 with a crushing majority. Protesters’ resent grew with the government’s decision to make the changes to the criminal code bypassing the parliament and issuing the decree in the middle of the night, ignoring the popular discontent with law changing project in the previous weeks. A recurrent slogan in the squares was in fact “At night like thieves!”1.

I joined the protesters in Victoria Square on the 1st of February. It was around -5 C degrees. My toes froze after 20 minutes. I could not stay more than one hour. Nevertheless, the cold weather was not the only, nor the defining reason for such a short stay – the following days the weather was actually warmer. It was the ideology on the square that frustrated me. This ideology, based on the pillars of anti-corruption, anti-communism and national pride, has been instrumental in the struggles inside the capitalist class in the past decades. In one hour I heard just three slogans: “Thieves!”, “PSD, the red plague!” and “DNA come and take them!”. Moreover, most nights of protest ended with a collective singing of the national anthem. The posters carried by the protesters were not very different either. I saw mostly signs with variations on the messages these three slogans carried or more humorous, apparently innocuous comparisons between the PSD leader, shit and popular political authoritarians (Erdogan, Kim Jong-un, and, yes, Ceaușescu, still) or fictional characters from games, movies and TV programs.

Despite the clear ideological leanings of the protests, it became difficult to claim there is such a thing as an ideological belonging of the movement. PSD and the media supporting it put forward several explanations for what is happening, blaming the mass movement on the president and the National Intelligence Agency (SRI – Serviciul Român de Informații) subordinated to him, on NGO’s funded by billionaire George Soros and on multinational corporations, which allegedly encouraged or even forced their employees to take the streets. Protesters reacted as always in the recent protests by refusing to engage in a critical reflection on the ideology of these mobilizations. Instead they claimed that protesters have differing social backgrounds and what unites them is the common request for the repeal of the decree. Trying to argue differently with the people in the square became almost impossible, because it would immediately end in allegations of affiliation with PSD. I do not contest the fact that plenty of those occupying the square do not subscribe to any particular ideology, but in practice they participate in the articulation of a new capitalist hegemony.

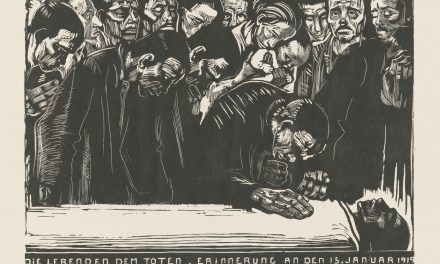

Why after 28 years of market reforms led by PSD, which governed for almost half of this period, do most Romanians think this is a communist party? How did a prosecuting department specialized in high rank corruption cases become one of the most praised institutions in this country? Why are anti-communism, anti-corruption and national pride the only signifiers able to mobilize such great number of citizens? There are no easy, short answers to these questions. But the weakness of left-wing political groups is key to understanding what is happening.

Communism was, and to the generation coming of age in the 1990s still is associated with forms of authoritarianism imposed on everyday life. For some of the older generations it is associated instead with periods of welfare. Nonetheless, it gradually came to be used also in a more narrow sense. It started to refer to the former party nomenclature permeating in the post-1989 political parties. This holds especially for PSD, which allegedly concentrates most of them, despite their lack of ideological commitment to communism. This latter allegation though emerged from struggles within the ruling class. These were struggles between most PSD party members, promoting a slower pace of market reform, keeping to a minimum welfare programs and supporting national capital, on the one hand, and liberals pushing for the shock doctrine, the cutting of social welfare and supporting global corporate capital investments, on the other.

In recent years the distinction between PSD and the liberals became less obvious. PSD has also made cuts to social welfare and curtailed global corporate capital. Like Victor Ponta for example, social democrat prime minister in office between 2012-2015, who welcomed US oil giants to explore shale gas reserves. In fact in the past decade the political agendas of the social democrats and of the liberals have become less distinct, with the former resembling more the latter. Despite that, the equivalence between PSD, communism and authoritarianism remains.

The weakness of a left to carve a distinct position from state socialism before 1989 and from the two options offered by the capitalist class which emerged from the ashes of Ceaușescu’s regime, is mostly responsible for the conflation of communism with authoritarianism and later on with PSD.

This conflation resulted in sidings with either of the two ruling class factions, causing a split in society and rampant tensions in the past years between two sides. On one hand, the poor and some of the precarious, which constitute around 2/3 of the Romanian society, sides with PSD because of some minimal social security measures beneficial for them that the party is still willing to maintain. On the other hand, PSD and by affiliation communism became the symbol of a retrograde authoritarian system that has to disappear. Much of the educated urban youth, employees of the IT&C, financial services and creative sectors – the majority of which are also precarious, entrepreneurs, as well as the private and public sector managerial class, sides with the latter view. In the square it was this side of society that prevailed.

Together with communism corruption became a tool in the same struggle. Although it was established in 2002, when PSD was still in power, DNA gained public fame after 2004 when a liberal coalition took power and the chief prosecutor of the agency opened files against important PSD leaders, amongst which also former PSD prime minister Adrian Năstase. In 2005 another prosecuting institution fighting corruption was established, namely the Department of Inquiring Organized Crime and Terrorism (DIICOT – Direcția de Investigare a Infracțiunilor de Criminalitate Organizată și Terorism). The indictments and condemnations of politicians involved in the privatization of former state companies and restitutions of properties that followed gave a sense of social justice to the majority of Romanian citizens. Notwithstanding, the social justice sentiment which the anti-corruption agencies provided obscured the selectiveness of the anti-corruption apparatus. In the absence of a powerful left appropriating the anti-corruption discourse, as in Latin America’s left-wing populisms, liberals have transformed the fight against corruption into a fight against PSD and its clientele. Consequently the poor and precarious siding with PSD started being demonized for their allegiance in the media and in everyday life.

The two factions of the ruling class have struggled also on a terrain defined by the vague idea of national interest. Ever since the mid 19th century formation of the Romanian state, the bourgeois class articulated the national interest in relation to the state and supported the flourishing of national culture in the arts and education. Contrary to what is often believed, the socialist regime did not discourage this complicity between state and national interest. Instead it promoted it to almost grotesque levels. The weakness of the Romanian left throughout modern history led to a majority of people, even amongst the poor and precarious, identifying first and foremost with the national interest promoted by the bourgeois and socialist states, before identifying with their class interest. For this reason national pride becomes a unit of measure for the commitment to the national interest and for the majority it is crucial that the parties prove this commitment. PSD has tried discursively to show this commitment by claiming that some international forces want to intervene in national affairs, bordering conspiracy theories when allusions to George Soros and multinational corporations were made – not only during the protests but even during the presidential elections campaign of 2015 and the parliamentary elections of December 2016. But the people believe that the corruption of its leaders on the expense of the public budget has proved the opposite.

It is true that in the past 10 years a wave of left wing independent thinkers and activists emerged: two groups of housing rights activists in Bucharest and Cluj-Napoca, some social centers in the same cities, two more recent workers’ rights groups, two publishing houses and several online platforms. But their social reach remains weak to non-existent and their unity is in shambles. Moreover the majority of the left oriented people have refrained from the current protests. And it is understandable why. The left has to face the historical legacy of its weakness, the ingrained priority of national interest over class interest in the people and the lack of financial resources to develop. These issues cannot be overcome by taking the streets and trying to redirect ideologically the movement with different slogans and banners. The 2012 anti-austerity protests, the 2013 protests against the gold mining project at Roșia Montană and the anti-fracking ones in the same year at Pungești proved that left voices can easily be suppressed by anti-communist, anti-corruption and national pride groups. But refusing to join the protests would also be a sign of weakness. Regardless of their suppression, the left voices participating in the recent years’ protests have shown the educated urban youth’s appetite for a progressive, equalitarian ideology. Although not numerous and weak, new initiatives have sprung and more people have engaged with some form of leftist ideology, be it moderate or radical. And this is also the merit of those criticizing capitalism straight from the streets.

Ironically on the night of the 3rd of February, while 150.000 people were protesting in Victoria Square, 3 km away in the city center 15 Roma families were being forcefully evicted. The local police took them out of the house under the pretense it was no longer safe to inhabit the building they were renting. Yet, there was no prior notification given to them and the temporary housing offered was going to split the families, women and kids were supposed to go to a shelter and men to another. On top of that, with no secure income, there was no guarantee they will receive social housing afterwards. This case was exemplary of the past decade’s gentrification of the city center, which saw many vulnerable Roma families thrown on the street in order to make place for parking lots or prime real estate. The Victoria Square protesters showed no signs of solidarity. The weakness of the left is the reason why. How to make it strong is still something to figure out or wait for while celebrating 100 years since the October Revolution, in the streets.

1Even though on the 5th the government issued another decree, which cancels the previous one, some legal counselors claimed that this would not solve the problems opened by the first decree. Moreover the government did not give up the idea of changing the criminal law and wants to send it to the parliament as a law draft. Protesters are now asking the government to resign.

Even though on the 5th the government issued another decree, which cancels the previous one, some legal counselors claimed that this would not solve the problems opened by the first decree. Moreover the government did not give up the idea of changing the criminal law and wants to send it to the parliament as a law draft. Protesters are now asking the government to resign. ↩